By now, everyone’s head is spinning, including mine, with the number of new frameworks and exposure drafts of sustainability disclosure requirements. With the hype being harmonization, decision-USEFULNESS, simplification, comparability and yes, interoperability, we might all be fooled into thinking that the life of a reporter will suddenly become a bed of roses. Let me correct that assumption. Perhaps a bed of nails might be a better analogy. Ha-ha. Better stock up on ice cream.

The winds of change are whooshing in three standards that will influence reporting in the coming years. Much has already been shared to explain and interpret these new whooshes, but I keep getting asked to share my take on things so here are some preliminary thoughts.

IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standard: So far, there are two draft documents for public consultation until July 29,2022

IFRS Standards, created by the newly created International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), are intended to be ratified by country jurisdictions to become law, in the same way as IFRS accounting standards are applied. These standards are geared to those who consider sustainability as an element of enterprise value creation only insofar as it affects the financial interests of those who fund and invest in companies.

European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS): The proposed draft for consultation by August 8, 2022, includes a suite of standards required under the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) proposal that covers the full range of sustainability matters - environment, social and governance - as developed by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG). These standards, after conclusion of the consultation period and subsequent modifications, will become law, affecting around 50,000 large and listed companies in Europe. The ESRS are designed to address the needs of all stakeholders, not just those with a financial interest. In the next phase, EFRAG intends to publish a set of sector-related disclosure requirements (as they obviously have budget to spare – SASB standards and the ongoing GRI sector standards clearly aren’t European enough). When ratified, the intention is to apply ESRS to disclosures from publication year: 2024 (on a phased basis).

U.S. SEC Climate-Related Disclosure rules for the inclusion of climate related risks and metrics in annual reporting on Form 10-K. This is another investor-focused initiative and will apply to listed companies, with a phased implementation starting from filing year 2024.

Let’s not forget also GRI’s Sustainability Reporting Standards: The revised GRI Standards structure including the new Universal Standards kick in for reports published in 2023. GRI are voluntary standards that are not expected to become law. GRI is keeping behind the scenes when it comes to the EFRAG and ISSB developments, signing collaboration agreements with both, relying on its historical positioning, having driven sustainability disclosure for the past 30 years, well before the EU or any investor community even knew how to spell ESG. GRI may now have succeeded to the point of irrelevance, having created the conditions in which companies may bypass its standards and disclose only what the new laws will require. While the EU standards build on the basis established by GRI, the ISSB standards do not.

Richard Howitt, a long-time influencer in the European sustainability disclosure space, recently set out the forces for convergence and divergence in these new EFRAG and ISSB standards. With only the teeniest smidgeon of optimism regarding whether both the European and the international sustainability reporting standards will actually move in the same direction, he sets out a 10-point plan for better cooperation. Good luck with that.

However, even if we end up with two sets of different standards (ESRS and IFRS/ISSB) (hint: we will), it’s not ever going to be an either/or. Companies in ISSB jurisdictions have stakeholders beyond the financial community and will not be reasonably able to limit themselves to financial-related sustainability disclosures. As we have seen time and time again, it’s the non-financial community that has driven disclosure on specific topics, and this will continue to be the case. This is where GRI claims its relevance – as a complement (or precursor) to finance-related sustainability disclosures as well as being the basis for non-financial disclosures.

Before we do a deep-dive into each of these changes and what they mean for reporters, alongside the many other reporting demands that companies accommodate – local SEC rules in different countries, disclosure demands from rankers and raters, voluntary-non-voluntary frameworks such as TCFD, CDP and PRI, EU Taxonomy, SDG etc. – let’s look at the overarching directions that seem to be emerging.

Materiality: The Star(s) of the Show

We have seen an explosion in materiality related terms – double materiality, blended materiality, nested materiality, ESG materiality, financial materiality and more recently, impact materiality. Materiality is apparently one of the most versatile words in the sustainability reporting lexicon. As I was writing, I even stumbled across a new term (though I doubt it’s likely to catch on): sesquimateriality. I even had to look up the definition of sesqui. This brilliant review by Frederick Alexander (The Shareholder Commons) takes us through the rationale for challenging the ISSB approach on ESG information that affects (only) enterprise value, saying that material beta (non-financial) information is just as necessary as material alpha (financial) information both for investors and for society. He writes: “On its face, the exclusive choice of enterprise value as the measuring stick for materiality means the standards will only be useful for investors who want to use environmental and social data to determine how a particular company will perform financially, in order to decide whether to buy or sell it, or perhaps to use their shareholder rights to push the company to change its practices to improve future cash flows. In light of the diversification mandate of Modern Portfolio Theory, and the importance of beta to diversified investors, this anachronistic hyper-focus on enterprise value is troubling.” Read this article. It’s excellent. (Even though the terminology is a bit of a mouthful). Essentially, the conclusion is that ISSB adopters should report more broadly on impacts and not limit themselves to the narrow scope of ISSB.

A similar point was made by sustainability thought-leader Andrew Winston, who bemoans the use of the term ESG instead of sustainability. He says: Seeing all things through the lens of markets and the quest for shareholder maximization is largely how we got into this mess in the first place. We’ve put profits above literally all else, and it’s leading to ecological collapse and vast inequality……. Just as fossil fuel companies should not lead the planning of our energy future, it seems unwise to let finance lead the journey to a humane, more just, less greed-filled form of capitalism.

ISSB picks financial materiality in its proposed IFRS S1 General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information. The materiality scope in IFRS S1 standard includes the following guidance:

The objective of [draft] IFRS S1 General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information is to require an entity to disclose information about its significant sustainability-related risks and opportunities that is useful to the primary users of general purpose financial reporting when they assess enterprise value and decide whether to provide resources to the entity.

Sustainability-related risks and opportunities that cannot reasonably be expected to affect assessments of an entity’s enterprise value by primary users of general purpose financial reporting are outside the scope of this [draft] Standard.

ESRS opts for double materiality – making the distinction between impact materiality and financial materiality. The materiality scope in ESRS 1 General principles includes the following guidance:

The undertaking shall report sustainability matters on the basis of the double materiality principle. Materiality is to be understood as the criterion for the inclusion of specific information in sustainability reports. It reflects (i) the significance of the information in relation to the phenomenon it purports to depict or explain, as well as (ii) its capacity to meet the needs of the stakeholders of the undertaking, allowing for proper decision-making, and more generally (iii) the needs for transparency corresponding to the European public good.

Double materiality means that if a topic is material EITHER from an impact standpoint OR from a financial standpoint, or of course, both, it must be included.

Impact materiality is defined as: connected to actual or potential significant impacts by the undertaking on people or the environment over the short-, medium- or long-term, and covers upstream and downstream value chain impacts.

Financial materiality is defined as: triggers or may trigger significant financial effects on undertakings, i.e., it generates or may generate significant risks or opportunities that influence or are likely to influence the future cash flows and therefore the enterprise value of the undertaking in the short-, medium- or long-term, but it is not captured or not yet fully captured by financial reporting at the reporting date.

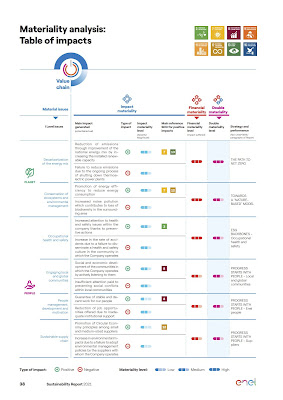

A shout out to Donato Calace of Datamaran who shared this example on LinkedIn of a new way of representing impact materiality and financial materiality in Enel’s 2021 Sustainability Report.

GRI stays with materiality: As you all know, GRI updated its definition of materiality with the new Universal Standards and this remains plain old materiality (or what the EU is now calling impact materiality) that is defined as: topics that represent the organization’s most significant impacts on the economy, environment, and people, including impacts on their human rights.

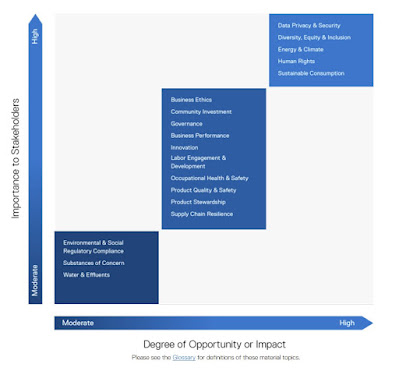

The irony is that most reporters have misrepresented materiality in GRI reporting, showing materiality matrices with one axis being the “interests of stakeholders” and the other axis being “importance to the business”. This is sort of double materiality by default, not by design, and it’s not always clear whether the impact on the business is the result of a considered analysis.

For example, Mondelez 2020 ESG Report shows importance to stakeholders and influence on business success, not size or significance of impacts.

Dell Technologies FY2021 ESG Report, on the other hand, shows importance to stakeholders and degree of impact, as defined by GRI Standards, i.e.: impact materiality.

What’s missing in materiality: The overarching issue with materiality assessments is of course the lack of standardized methodology. How does a company actually assess the severity of its positive and negative impacts on society and the environment? The guidance in the standards, old and new, is high-level and directional. Every company does it in a different way, some more structured, some less. Generally, that materiality assessment is the result of surveys and stakeholder opinion, with little consideration of the degree of impact. The results you get depend on the stakeholders you consult and what you ask them.

Almost all materiality processes are not fully transparent. Even the presentation of Enel noted above describes a series of processes… first we analyzed… then we analyzed… and a set of approaches: “The main impacts identified, both negative and positive, were considered respectively according to their degree of severity or magnitude and probability, in the case of potential impacts.” Well, that doesn’t tell us very much, really.

GRI guidance recommends assessing the severity of an actual or potential positive or negative impact by analyzing scale (how grave/beneficial the impact is), scope (how widespread the impact is) and irremediable character (for negative impacts, how hard it is to counteract or make good the resulting harm) as well as the likelihood of the potential impacts occurring. Given the fact that materiality is so fundamental to how sustainability disclosures are defined and developed, I have been advocating for years for the development of a standard that would provide a structure and logical process for materiality assessments, and enable understanding of how impacts are prioritized. The lack of attention to this point in both the ISSB and the ESRS (I gave up on GRI long ago) is a missed opportunity to align companies on how to prioritize material topics for sustainability disclosures as the new standards are being developed.

Getting Closer to the Money

Both standards move sustainability disclosure closer to financial reporting, in an attempt to raise the status of the former to equal or near equal to that of the latter. This is a bit of an uphill battle. Sustainability disclosure may never be anything more than a poor relative in the eyes of the financial wizards, but it’s true that the life of financial analysts will be easier when both types of reporting show up on the same playing field. This has two main implications:

First: Reporting period and publication timing

Both ESRS and ISSB require for sustainability disclosure to align with the period and timing of financial disclosure.

ESRS 1: The undertaking shall retain a reporting period in its sustainability report consistent with the one retained for its financial statements.

IFRS S1: The sustainability-related financial information must be for the same reporting entity as the financial statements and published as part of its general purpose financial reporting. This means the information must be disclosed at the same time as the financial statements.

This is logical development, and not just for the money folks. Too many sustainability reports are published so late after the end of the reporting period, they are already stale before you even get to page one. The late publication of sustainability information may result from a lack of urgency and discipline in organizations for sustainability information, and/or a lack of infrastructure in gathering and organizing data. For sustainability to be better integrated and for decisions to be made in real time (to advance sustainability, not just for reporting), this needs to be professionalized. No more endless excel files for data collection, no more begging colleagues for collaboration, no more scrambling around at the last minute for missing data points. The new standards will force companies to get onto the same timeline as financial reporting, and this will require a step change in both process, resourcing and supporting technology. That’s good for the financial community and, arguably, better for company decision making. But it won’t be easy for most.

Second: Auditing and assurance

The other longstanding complaint about sustainability information is that most of it is not externally assured and therefore confidence in its accuracy is low. The move to auditable and audited sustainability information is also a good thing. This addresses more than verification of GHG inventories or climate reporting, which many companies now externally assure, but all the material quantitative and much of the qualitative information that companies disclose. With sustainability being incorporated as part of financial disclosures (ISSB) or management reports (ESRS), they will be required to be assured to at least a limited level. What a gift for the accounting/assurance firms who are now gearing up for a fuller workload and an even fuller revenue stream. And companies that have never assured data in the past, be prepared for some surprises in your audit results.

Silo Busting: Sustainability Connectivity

The new standards whoosh in the concept of connectivity between financial and ESG information. This is not so new. It was attempted with the six capitals approach of the Integrated Reporting framework, but it never made real headway in practice in demonstrating true linkage, I believe. With both ISSB and ESRS standards emphasizing the principles of connectivity, we may start to see some new tools to help this understanding. The EU Taxonomy is perhaps one, and the scenario-planning approach that became the high-jump of the TCFD guidelines is a driver of more holistic thinking about the way the risks will affect the numbers. ISSB is also planning the release of the IFRS Sustainability Disclosures Taxonomy (yes, they have a big budget too).

IFRS standards allow information to be referenced i.e., it can be part of a separate document. ESRS requires all information to be contained in the management report… a throwback to the days when GRI reporting purported to have sustainability information “all in one place”. Today, GRI reports are often a menu of references to many other documents, making it difficult to actually track what’s being reported.

However, the focus by both on connected information and impacts is explicit:

IFRS S1: An entity shall provide information that enables users of general purpose financial reporting to assess the connections between various sustainability-related risks and opportunities, and to assess how information about these risks and opportunities is linked to information in the general purpose financial statements.

ESRS 1: The undertaking shall adopt presentation practices that promote cohesiveness between its sustainability report and: (a) the information provided in the other parts of the management report ... (b) its financial statements; and (c) other sustainability-related regulated information. …

The implication for organizations is not to be underestimated here. Some might see it as an elevation of the role of the CSO to the level of the CFO. Others might see it as the gobbling up of the CSO by the CFO. Either way, it will be interesting to see how this develops in corporate organization structures. Both standards are saying that the sustainability voice must be heard more clearly. It’s no longer just about disclosure. It’s about strategy that, for the first time in many companies, should actually integrate sustainability thinking, and not as a series of projects (emissions reduction, diversity and inclusion etc.) but as a way of doing business through the entire value chain and reflecting the interconnectedness of it all on society, the environment and on the sustainable profitability and growth of the company. No more part-time sustainability leadership. No more adding it on to an already busy executive’s to-do list. The new standards give more oomph to the role of sustainability leadership in an organization and it must be resourced appropriately.

History Lesson Over. Enter Goals, Pathways and Glidepaths

The sustainability report as a history book is now a thing of the past. Sustainability disclosures of the future are expected to be a set of promises, a pathway to deliver and an update on progress. The TCFD four-part model of Governance, Strategy, Risk Management, Metrics & Targets has become a useful role model, leading to more of a forward-looking disclosure than has ever been common practice. ISSB’s draft Climate Standard IFRS S2 adopts this approach in full, possibly an indication of things to come in future ISSB standards. The ESRS standards also emphasize the need to report on the future: ESRS 1 When defining its action plans and setting targets, the undertaking shall adopt time horizons that reflect its strategic planning horizons and resource allocation plans. Also, in ESRS_E1 Climate Change standard, companies are required to disclose plans to ensure the business model and strategy are compatible with the transition to a climate-neutral economy and with limiting global warming to 1.5 °C in line with the Paris Agreement.

This is another good development. Way back in 2018, when we all lived in a very different world, I wrote about the importance of targets in sustainability reporting. I continue to find many reports that talk a great sustainability story but do not back it up with clear commitments. And I don’t mean just an emissions or energy efficiency target, but a set of targets that underpins strategy and promises progress across a range of environmental and social impact areas. But if in 2018 I talked about setting targets, today, it’s about setting targets AND (alert: jargon ahead) transition pathways. We all want to know not only what your target is, but how you plan to deliver.

There is SO MUCH MORE to say about these new standards proposals. I didn’t even mention the new Climate Disclosure Rules of the SEC. I am hoping to carve out enough time to post detailed analyses and commentaries about the ESRS and ISSB drafts, and the SEC new rules in the coming month or so. In the meantime, on the whole, the developments are positive. They are raising the bar for sustainability disclosure and driving the integration of sustainability thinking and practice to become the new business as usual. While I believe the ISSB standards are not tenable as disclosures for stakeholders (as opposed to shareholders), they were never intended to be. On the other hand, ESRS has totally gone to town with their standards: 560 pages of detailed requirements and guidance may be just a little too much for companies to handle.

And will all this make life easier for reporters? Hmmm, not so much. The interoperability approach only goes so far and there will still be multiple and more extensive disclosure demands. New legally-binding standards will require greater compliance effort than the largely voluntary disclosures to date. Digitization with new taxonomies, assurance and scenario analysis will add new challenges to the mix.

Ultimately, the question is whether all this information will actually be used in a meaningful way to further us along the path to sustainable investment and a sustainable world, or whether it’s all just spin. Will ISSB make more money for investors in the long run? Will ESRS help make life better for all Europe’s grandchildren? Will ice cream continue to be the solution to everybody’s problems? I know the answer to the last question. The jury is still out on the former two.

elaine cohen, GCB.D: ESG Competent Boards Certified (2021), Sustainability Strategy and Disclosure Specialist, former HR Professional, Ice Cream Addict. Owner/Manager of Beyond Business Ltd, an inspired Sustainability Strategy and Reporting firm having supported >140 client reports to date; author of three books and several chapters on Sustainability Reporting and the Human Resources connection to CSR; frequent chair and speaker at sustainability events and judge in several sustainability awards programs each year. Contact me via Twitter , LinkedIn or via Beyond Business